Nobody Wants This

Part I

Nobody plans to become a campaign manager.

Most of us saw a ladder and grabbed it. I did that in New Jersey in 1999 and went 0-3 across three years, which turned out to be the optimal start to a consultant career.

The gut punch isn’t about vendors, spending, or concentration. It’s the shape of the funnel: 51% of campaign managers work one year and disappear. I stayed three years. My salary was $2k per month and I often slept in our campaign office, smelling of damp sewage in a dying strip mall in Middlesex County NJ, surrounded by highways to anywhere else. The swamps of Jersey are real, and they are spectacular for training political operatives.

Nothing about this felt normal at the time, but the math says this was pretty standard. Only 5% make it to seven years before leaving FEC visibility. The median campaign manager works 1.8 years before disappearing forever. This is a bus station, not the final stop.

What’s changed is that we no longer produce or sustain large numbers of experienced managers, and I’ve spent the better part of 2025 wondering why. This analysis focuses on campaign managers because they are the first role in political work where people attempt to make a career. But the forces it reveals… flat pay, geographic escape as the only raise, alumni gravity, and rational exit, apply to nearly everyone who works in politics.

The Tightest Funnel

Campaign managers face the steepest survivability curve in American political life:

51% work one year and disappear

19% exit after year two

12% exit after year three

13% make it four to six years

5% survive seven or more

Median career: 1.8 years

I could not find another profession in American public life with such a steep, narrow path to longevity. The general political workforce is volatile, and campaign managers are the most volatile of all. The hundreds of thousands of people might love knocking door to door for $100 every two years, but the campaign managers? They pass through the bus station faster.

The nearest analogy? Child actors. Seventy percent quit before age 25. Of the ones who survive, some get rich, some go to jail, and most need therapy. But campaign managers are even more exposed; their careers hinge on the survival of their category, the whims of donors and committees, and the strength of their state ecosystem, all of which weakened during the last decade.

Win Rates and the Money That Doesn’t Follow.

The dataset reveals a correlation between campaign management experience and campaign outcomes. This mirrors what happens to political staff broadly:

First-time staff: 34% win rate

2-3 years experience: 42% win rate

4-6 years experience: 51% win rate

7+ years experience: 58% win rate

The win rate nearly doubles from rookie to veteran, but much of that is actually that well connected and funded campaigns win, and they get to hire more experienced staff.

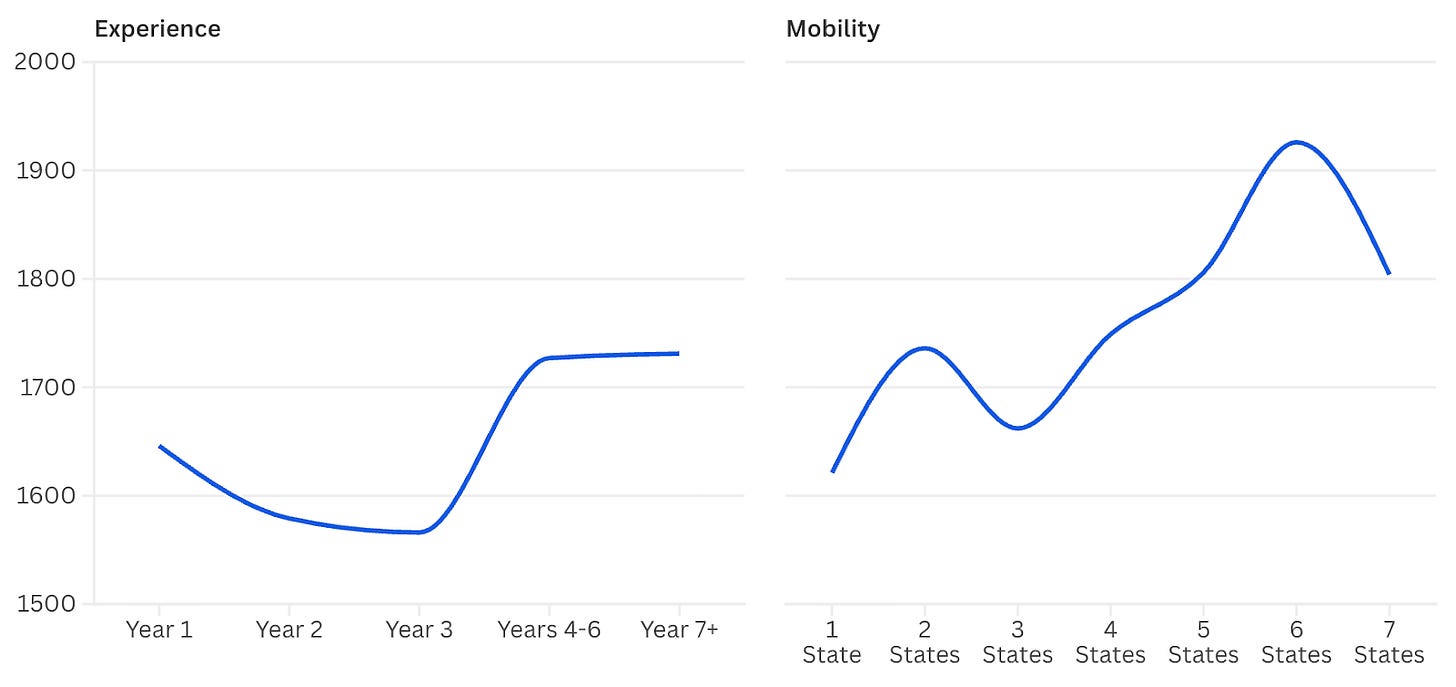

And then there is the money. Here’s what nobody tells you about campaign management: there is no raise for experience. Using cohort-level averages across 300,000+ individuals:

Year 1: $1,646 per engagement

Year 2: $1,579

Year 3: $1,566

Year 4-6: $1,727

Year 7+: $1,731

Translation: staff with seven or more years of experience, the ones who win 58% of the time, who carry institutional memory, who mentor everyone else earn essentially the same per engagement as first-time staff who win 34% of the time.

There is no ladder here. There is no compensation growth. There is no financial reward for accumulated expertise. The profession does not value career survival. Staying in campaign management is economically irrational unless you escape your home state or possess a unique form of self-hatred.

The Only Premium: Geographic Mobility

If experience doesn’t increase pay, what does? Geography.

Average compensation by distinct states worked:

1 state: $1,621

2 states: $1,736

3 states: $1,662

4 states: $1,749

5 states: $1,806

6 states: $1,926

7+ states: $1,804

The only meaningful professional progression is correlated with fleeing the state. You don’t climb the ladder. You escape your local market and accumulate multi-state reputations. Staying local means staying commodity-priced. This explains the survivor population better than any other factor. Long-term managers aren’t people who got promoted. They’re people who left town to double the size of their network.

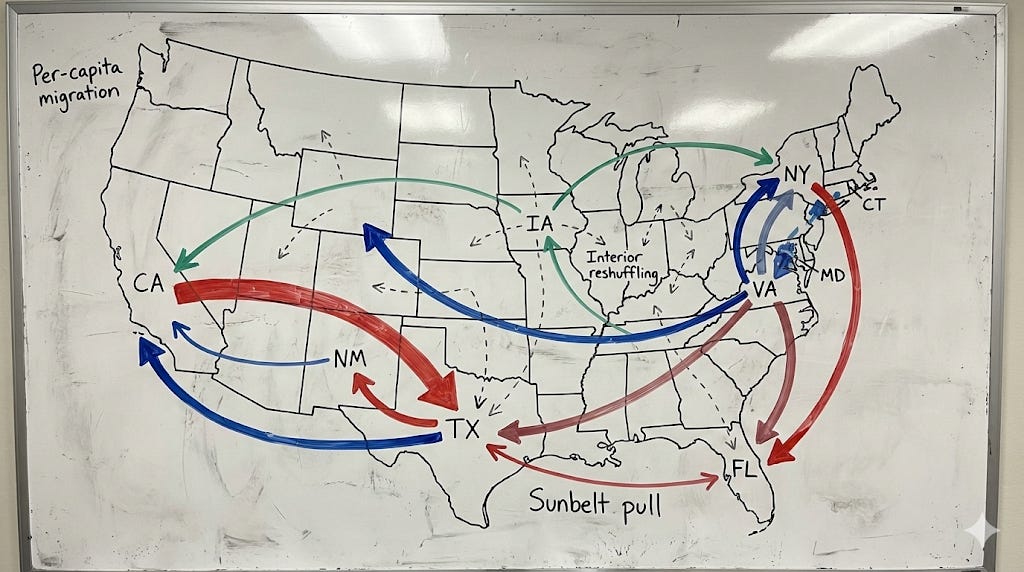

Tracking first-to-second cycle movement shows that 26% of managers who keep working after their first cycle leave their home state immediately. That rate is not evenly distributed. Some states hemorrhage talent. Others hoard it.

When normalized per capita, Vermont, Alaska, Rhode Island, New Mexico, Louisiana, Iowa, and Kentucky export political staff at two to four times the national average. These are not amateur markets. They train great people fast and burn them out faster. Survival requires leaving. Those departures happen in the same patterns, over and over. Here are a few:

Patterns of Staff Migration

Oklahoma → Texas: One-way, high-volume early exit (1–2 cycles). Texas takes the bodies once they’re useful.

Louisiana → Texas: One-way and accelerating. There is no second rung on the ladder.

Vermont → DC / Virginia: Per-capita export leader. Vermont’s biggest export is political people who leave Vermont.

New Hampshire → DC / Virginia: You likely know exactly what time the Manchester to DC flight on Southwest leaves (30x weekly).

Rhode Island → DC / Massachusetts: Small-state staff flee permanently after first promotion opportunity.

Maine → DC / Massachusetts: See Rhode Island.

Iowa → Illinois: Being from Iowa is good for your career.

Wisconsin → Illinois / Michigan: Wisconsin builds strong campaign resumes, which are in demand next door.

Kentucky → Ohio / Indiana: The I-71 Royale.

Virginia (net inbound): Everyone’s first stop (including me).

Proximity to federal power creates durable staff retention. By contrast, Virginia, Texas, Florida, Pennsylvania, and the DC corridor absorb staff at scale. These states hire and retain more people. Layered committees, national vendors, permanent infrastructure, and donor density mean a lost race doesn’t end a career. It just moves you sideways.

This is why long-term professionals (probably like you) all sound the same when they tell their origin stories. The data shows that managers who work in three or more states earn 15–20 percent more per engagement and survive nearly twice as long as those who stay put.

The Kids Aren’t Alright

For twenty years, campaign management was shaped by a predictable apprenticeship ladder. The best managers came up through field ops, state party or caucus programs, coordinated campaigns, legislative leadership offices, political departments of major organizations, vendor-run field, polling, or data shops, and Hill, press and scheduling lanes.

The ladder weakened gradually through the 2010s and then collapsed one Silent Spring day in March 2020. Tens of thousands of staff were removed from the campaign manager pipeline at once in order to prevent the spread of a virus. The 2020 year produced few with traditional field management experience. The next year recovered the same way commuting to an office recovered: it exists in theory, but in truth, nobody is wearing pants.

This means the profession lost roughly one full generation of field-trained staff.

The Digital Trap

Digital, which I viewed as the final phase of my career path in 2010, turns out to be the most dangerous place for managers to launch a stable career. The data is brutal:

Digital-first managers show 3.8× higher burnout rates than managers who entered 2008-2012

Vendor-trained managers show just 11% long-term survival vs. 18-34% for party-trained staff

Turnover this fast makes sustained professional development impossible.

Staff who enter through digital often find themselves without institutional homes two years later

State Party Collapse

I think a lot of people would be surprised to see the sad state of any state party office. Once the reliable incubators for future managers, they lost funding, staff capacity, and continuity due to campaign finance law changes and evaporation of local civic life. Most now operate as a shadow of their early-2000s scale.

The result today is a generation of managers who enter the business without the experience that defined political careers for decades. Their first management role is often their first exposure to the deep state of a campaign. Going from social media manager to campaign manager is a very different world than field director to manager, and the career mortality rates prove it.

The Covid-Baby Manager Class

The data shows an inflection point in the campaign manager pipeline coinciding with spring 2020. You are about to meet the least prepared generation of campaign managers in history, the Covid Babies.

The median campaign manager is 27 years old. Most people enter professional politics at 22. (The distribution clusters tightly: most managers assume the role between 26 and 30.)

And what were we doing five years ago? Banning field. The result: complete collapse of the specialty, removal of in-person organizing, state party staff contraction, disappearance of multi-layer apprenticeship tracks, and the thinnest institutional memory period in the dataset. COVID erased the knowledge of how to run a proper GOTV operation, and it’s about as likely to come back as Yiddish.

This is the first COVID-trained manager class with no field experience, no apprenticeship model, atrophied local capacity, remote-first culture, and weakened institutional memory. All those kids who would have headed field ops for Washington County? They instead learned how to post on Facebook.

Here is the reality for new campaign managers in 2026:

Weakest prospects for a long-term career path. The 2020-2024 entrants already show the lowest projected multi-year survival: approximately 18% compared to historical norms of 32%. Their expected career length is just 4.2 years, the lowest on record.

Thinner mid-level mentors. The middle class of managers (3 to 6 years) will be underpopulated well into the 2030s. Anyone with field experience should ask for a raise right now.

Higher operational load on campaign veterans. The 5% of managers with 7+ years will shoulder more responsibility as the stabilizing cohort. They’ll be the grey beards before 40.

Greater geographic imbalance. The twelve states with surviving infrastructure will absorb and train most of this cohort; others have atrophied to varying degrees. (More on this later.)

Nothing will impact the industry as much as what we are about to experience. The failure of field in 2020 and the collapse in political telemarketing in 2008 don’t compare. There are a whole lot of bus drivers about to show up at the bus station who have never actually driven a bus. On a road. With people.

Amen on the death of State parties. That worries me a lot.

This is incredibly interesting. Mirrors my experience. 4 years of hard work in one state, and moved on due to low pay and starting by a family. Still involved on the periphery but no longer source of income. Thanks for writing!